Did Samuel Slater Dress Up as a Woman

This story is about espionage, treason, a covert escape, and an ocean voyage. It's also a story about founding an American factory that would be the impetus for America's industrial revolution. The story is true. The narrative represents the author's reimagining of the events.

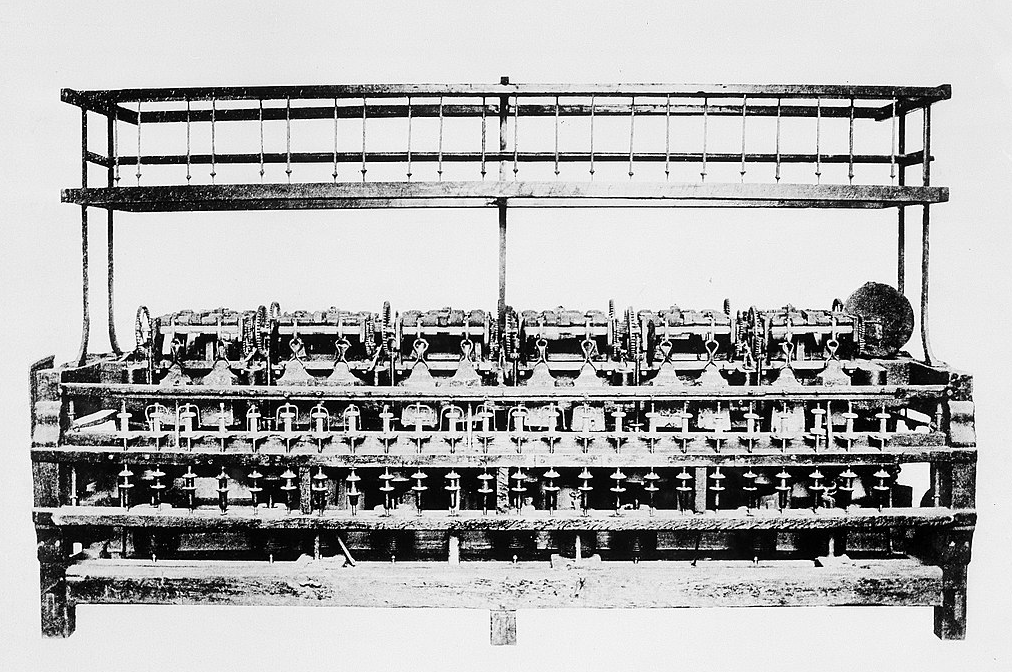

Image courtesy Wikimedia.org

Samuel Slater shifted his weight from foot to foot as he stood in line. His attempts to appear relaxed made him increasingly fidgety. He feared the emigration agents would discover his ruse—if caught, he would not be sailing to America. Rather, he would be arrested and charged with treason. He would go to prison. Worse, he could be hanged. Slater fought the images playing in his mind: walking up the thirteen steps of the gallows, covering his head with a hood, placing a rope around his neck. A short drop, a snap, and—what?

His chest tightened as he resisted the urge to run. Instead, he focused on breathing, inhaling deeply through his nose and exhaling through his mouth. He imagined his childhood and the dreams that led him to this point.

Child Labor, War, and Domestic Unrest

Slater's thoughts settled onto his first day working at the Strutt cotton mill in Belper, Derbyshire. He was ten years old, and he was anxious. As he toured the factory, alternately wringing his hands and picking at this face, he was alarmed by what he saw. Younger children started at the factory as scavengers, crawling beneath the active machinery. They would clear away dirt and dust and pick up bits of cotton that had fallen underneath. Unfortunately, crawling among the moving parts was dangerous, and accidents were common. The machines could grab fingers and hair, break bones, or worse. But his pay of ten cents an hour might make his efforts worthwhile. At ten hours a day, six days a week, he could take home twenty-plus dollars a month to his parents and seven siblings.

You see, their family farm was struggling. In 1778, all of England was struggling. The wars with America, France, and Spain hampered trade and curbed the domestic economy. King George III could not keep his government working—administrators repeatedly quit.

Apprenticeship and Roadblocks

Samuel Slater's world, though, was stable. He had a loving family, a job, a home, and enough to eat. He was well-liked by his employers and his co-workers. Then, at age 14, his father died. Slater was formally indentured as an apprentice to Strutt—a seven-year appointment. A fast learner with good math skills and an impressive memory, he was promoted to factory superintendent ahead of Strutt's four sons. Slater kept the machines running. When something broke, he fixed it. He was a gifted mechanic.

Though not yet 21, Slater realized that he had reached the limit of his upward mobility at Strutt's. After all, Strutt had four sons. Certainly, one—or more—would assume ownership and management of the cotton mill. He wondered how long he could be satisfied working in the same mill, day after day. Could he last forty years? He found the work tedious. He became weary of workers who didn't pay attention, and the Strutt boys, who would ask for help solving a problem and then ignore his advice. He had responsibilities but no authority to change anything. From time to time, he would reflect on his plight. His teeth would clench until his jaw hurt as he replayed events in his mind.

Hatching a Plan

One afternoon, the howling of the Strutt boys attracted his attention. But, it was the newspaper ad that gripped his imagination. The Strutt's conversation was animated, punctuated by exclamations about "damned Americans" and "Hurrah for Parliament." Then, finally, the Strutts left the room with an air of finality, throwing the newspaper on a table. Slater picked it up and soon found the source of the Strutt's agitation and glee.

Inside the 1788 Philadelphia newspaper, the Pennsylvania legislature advertised for machinists to build cotton rollers and textile machinery in America. Furthermore, they offered a bounty of £100 to machinists who would bring their expertise to the new nation. The report was the source of the Strutt's consternation. Their glee was caused by Parliament's enactment of a new emigration law designed to keep their technology at home. Anyone caught providing the Americans with textile technology would be arrested and charged with treason.

Slater had the expertise the Americans were looking for. Going to America would be a dream come true, but doing so would be risky. Still, the thought of going quickened his pulse and left him energized. He found it impossible to push thoughts of America from his mind. Dropping off to sleep at night, he visualized each part of the Arkwright textile machines and how they fit together. What were the fine details of each component, and how could they be manufactured? His goal was to memorize the construction of each machine. Because unfortunately, he couldn't write anything down or make any drawings. Doing so could have treasonous implications.

An Ocean Voyage

In 1789, Slater's apprenticeship was over, and he received his journeyman credentials. He was free to practice his trade anywhere in England, but his heart was set on starting anew in America. So, saying goodbye to his mother and family, he packed his bag and caught a stage to London.

While in London, Slater refined his plans. He booked passage to America, but the ship didn't sail for ten days. Reviewing his plans endlessly, he determined to hide his indenture papers and dress as a farmer's son rather than a mechanic. English emigration agents were very scrupulous, thoroughly searching each passenger to America. He could not give any indication that he was a journeyman machinist. He wrote a letter to his mother to be posted just before his ship sailed. In it, he explained his intentions. His mother was the only one who knew. Slater never spoke of his dreams to anyone for fear of discovery.

In line at the emigration station, Slater's reverie was broken when the inspector called out, "Next!" He moved forward to the inspection station, but his nervousness was apparent. When the agent asked about his trembling, Slater replied, "first time on a ship, sir. I'm frightened." The ruse worked. Slater boarded the ship for America. There would be no turning back. Once the ship landed, Samuel Slater could no longer return to England. After a voyage of sixty-six days, he landed in New York on December 7, 1789.

Image courtesy Wikimedia.org

A False Start

Slater quickly found employment at a New York textile mill. But, the machinery was not state-of-the-art, and the final product was sub-par. Convinced that America was in dire need of his services, Slater sought out other textile mills. He wrote Moses Brown, an industrialist in Rhode Island, seeking a position. Brown replied:

"We are destitute of a person acquainted with water frame spinning… If thy present situation does not come up to what thou wishest…come and work [with] ours and have the credit as well as the advantage of perfecting the first watermill in America."

Slater traveled to Pawtucket, Rhode Island, to inspect Brown's machinery. Brown promised a partnership if Slater could coax the machinery into producing usable thread. But, the machinery was a sketchy knockoff of the Arkwright mill Slater had used in England. There were no replacement parts and no system for training workers and machinists. Hopes of a partnership dashed, Slater reported to Brown that his machine could not be fixed. The only solution was to scrap it and manufacture one from scratch. It would take time to build the machinery and train operators to run it. Discouraged, Slater wondered what his next move would be.

Image courtesy Wikimedia.org

New Horizons

Brown, though, would not be deterred. Instead, he agreed to provide Slater with the resources to build American designed-and-made machines. Slater did this through memory and intuition. Included in his concept was a new spinning machine. There was a dire need for cotton thread in America, and other mills were not addressing the need. Instead, they focused on creating finished products for market. Slater envisioned meeting the demand by bulk-manufacturing thread. His approach worked. Slater's mill quickly became the dominant cotton-spinning mill in America.

In 1807 Slater, joined by his brother John, built a new factory on the banks of the Branch River in Buffums Mill, Rhode Island. Mass-producing thread required a large workforce, which required housing and amenities. So, Slater built homes, company stores, and churches for his employees. As a result, Slatersville became the model for nineteenth-and twentieth Century industrial towns.

The textile industry in the United States had grown to 62 mills by 1809, sixteen years after Slater constructed his first mill, with 25 additional mills planned or under construction.

Samuel Slater's skill and ambition paid off not only for him but all Americans. He automated the textile industry and devised ingenious production systems that shaped American manufacturing. His work was the impetus for America's Industrial Revolution.

In 1835, two years after his death, President Andrew Jackson dubbed Slater "The father of American Manufacturers." Back in Slater's home of Belper, Derbyshire, though, Englishmen called him "Slater, the Traitor."

Wayne Jordan is WorthPoint's Senior Editor. He is the author of four books: The Business of Antiques published by Krause Books, Antique Mall Profits for Dealers and Dabblers, Consignment Gold Rush: the Ultimate Startup Guide and Relocate for Less published by Learning Curve Books. He is a regular contributor to a variety of antiques trade publications. He blogs at sellmoreantiques.net .

WorthPoint—Discover. Value. Preserve.

Source: https://www.worthpoint.com/articles/collectibles/samuel-slater-treason-and-textiles

0 Response to "Did Samuel Slater Dress Up as a Woman"

Post a Comment